New DOJ guidance: focus on managers in your corporate compliance program (plus: dog jokes)

In case you missed it: the Department of Justice just released their 2019 update to their Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs document. It’s an update to the 2017 document that we previously roadmapped for you. [2020 update: the DOJ has updated their document again—find out what we have to say about it here.]

Not familiar with it? If you’re subject to US jurisdiction, or a US prosecutor attempting to exercise jurisdiction over you—so, like, you’re on Earth—you should be. It’s intended to assist prosecutors in deciding whether your compliance program was effective or not.

Put more bluntly: it tells you how to do your job.

So don’t be like the goofballs at the Compliance Week conference back in 2017—specifically, the ones who hadn’t bothered to read the last version but were still confident their program would pass muster UNDER THE THING THEY HADN'T READ (seriously, we took pictures).

You need to know this.

And hot take: there’s some great stuff here—and some clunkers, too.

I know! So smart!

This is our first cut, because we’re still digesting and unpacking this. If you want hastily slapped-together regurgitation of the text, there are law firm updates aplenty for that (OOH SICK BURN).

You come here, though, for deep analysis, weird analogies, and Vines. Like this one of a flying lawnmower set to Mariah Carey that makes me laugh every single time.

For today, we just want to focus on one thing that is actually pretty great: what this updated document says about managers.

Want to get the best manager training ever made? You should join Compliance Design Club!

Focus on managers—because they're riskier.

First, duh.

Second, this new document ramps up the DOJ's emphasis on ensuring that companies focus on the transactions, people, and processes that present the most serious risks.

And because your company has a delegation of authority, that means stuff done by managers and other senior folks—the people who have authority to perform risky transactions and processes in the first place.

Here are the most important brand-new quotes, emphasis mine:

“Have supervisory employees received different or supplementary training?

“Does the company devote a disproportionate amount of time to policing low-risk areas instead of high-risk areas, such as questionable payments to third-party consultants, suspicious trading activity, or excessive discounts to resellers and distributors?”

“Does the company give greater scrutiny, as warranted, to high-risk transactions (for instance, a large-dollar contract with a government agency in a high-risk country) than more modest and routine hospitality and entertainment?”

“Prosecutors may credit the quality and effectiveness of a risk-based compliance program that devotes appropriate attention and resources to high-risk transactions, even if it fails to prevent an infraction in a low-risk area.”

In short: focus on the really risky stuff.

And the good news is this: the really risky stuff is done by a small fraction of your overall employee base.

For example, at my last in-house job there were something like 100,000 employees and contractors, but only about 500 of us were director-and-more-senior; I was one of them. What the DOJ is saying is that those 500 were more important than the other 99,500, and by an order of magnitude.

Why? Because they have more authority and so can do more harm or good. They approve what others do and can do stuff themselves without needing approval. The DOJ is saying to focus on people like that and the things they do.

And I know, it sounds like “duh” when I put it like that—especially if you’re a lawyer—but the bad news is this: it is super easy to get this wrong in practice, even if you understand respondeat superior and agent/principal stuff backwards and forwards.

Why it’s so hard to focus on managers.

It is super easy to focus on the 99,500 instead of the 500 because:

- They report more concerns and ask more questions, so you’re always reacting to them.

- You want to build a compliance culture, and that makes you think you have to go for the largest number of employees.

- You know your senior folks are more sophisticated and assume that means they don’t need as much help or focus as the rank-and-file.

All of those are really understandable reasons, but they are also wrong, and that’s what the DOJ is saying here, too.

This is a matter of shifting your mindset and focusing on the right stuff. So, let's break these down.

First: yes, of course you should respond to concerns and questions from everyone. But no, the fact that you get a million questions on conflicts of interest from your shop floor employees does not mean that a shop floor employee having a conflict of interest is even a remotely serious risk to the enterprise.

Of course it’s bad if your rank-and-file do a bunch of dumb stuff, or steal, or whatever! But you can’t fix every problem. Your job is corporate compliance, not make-everyone-a-good-person compliance, which is good because the latter is impossible anyway.

So fix stuff the little stuff—or better, delegate it to someone else to fix—but do not let that noise pull your focus from what matters. Otherwise you fall into that “disproportionate amount of time . . . policing low-risk areas” bucket, and the DOJ is explicitly telling you to not do that.

Practically, this means that if you spend hundreds and hundreds of hours on a Code of Conduct annual training, but your financial approvals training for managers is just a post-it that says this:

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

...then you’re doing it wrong. You need to flip-flop your allocation of resources.

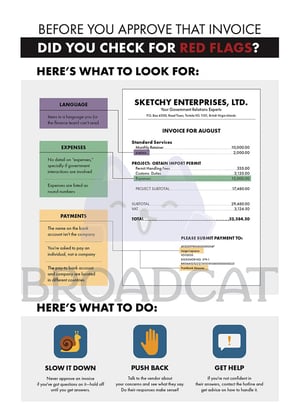

You need to spend less time on fuzzy all-employee stuff and more time on targeted stuff like this:

Want financial approvals training for managers? That and much more are available from Compliance Design Club!

And yes: you should build a compliance culture. But no, that does not mean you should spend all your time in your direct labor plants.

Why? Because companies are not democracies, they’re oligarchies.

(Except Broadcat. We are a cheerocracy.)

Put otherwise, there is this pervasive belief that corporate culture is primarily a bottoms-up initiative. I used to think this too. But now I run a company, and, uh...it's not.

If you want to build a compliance culture, get your 500 on board; that’s all you need. The 99,500 will follow, because the 500 are the people who hire, fire, and set the budgets and compensation and bonuses for everyone else—and if any of the 99,500 don’t like it, they’ll leave.

On the other hand, if you get the 99,500 on board but the 500 don’t agree, the 500 can wipe out everything you’ve done with a stroke of a pen or a click of a mouse.

For example, my team can spend hours and hours doing something they think is a great idea, but if I look at it and say “eh, I don’t like that,” it’s dead. That’s how companies work, and yours is the same.

Now, what happens if you can’t get your 500 on board?

Well, you don't spend all your time focusing on the 99,500 and hope that counts. (It doesn't, and the updated DOJ document makes that even more clear than it was before.)

No: you quit your job and go somewhere else where the leaders actually care about compliance and ethics, and you can do this because AMERICA.

(Want the "quit your job" thing unpacked? There's more on that in the questions at the end of this thing—go to page 28.)

And finally: yes, your senior folks are more sophisticated. No, that does not mean they have any clue what the fart they are doing in the context of compliance, nor does it mean they are somehow impervious to the overwhelming amount of ethical blind spots and justifications all people have for their own bad conduct.

That’s because being good and sophisticated at one thing does not mean you are good at other things. Knowing how to do something and knowing how to spot an ethics and compliance risk in that same “something” are two different skills.

Like, for example, here’s a compilation of dogs who are sophisticated at being adorable but terrible at walking down stairs:

More on point: at Broadcat, we've had folks jack our stuff, use us to pretty obviously skirt a procurement process, and blatantly game or breach our terms of use and agreements.

And all of those things were done by compliance professionals or someone working for them.

And being a "compliance professional" is kinda peak sophistication on compliance stuff, right? But it still happened.

I don't think a single one of those things happened with bad intentions—it’s because those folks thought of “compliance” as stuff like corruption and money laundering and conflicts of interest, and so it just wasn’t on their radar that what they were doing was a problem.

And that’s normal; that’s how we all are, and that’s why you have to focus on your 500 risky people, because being well-educated and sophisticated doesn’t mean you’re a wizard who doesn’t need help—even compliance people make compliance mistakes. We all do!

So yes, it is obvious that your rank-and-file need help when they make obvious, glaring mistakes. But their mistakes also don’t matter that much in the grand scheme of things.

It’s the mistakes your “sophisticated” people make that do, and that’s where your focus needs to be.

(And look: social media blah blah blah. Some rank-and-file says something dumb on Facebook and your company gets dragged on Twitter. I know, I know, it seems like a huge deal—but you'll be fine. On the other hand, if your company's "sophisticated" people are rotten, you won't be fine—you'll be Theranos.)

"UGH this question again?"

Here’s the takeaway: this probably is going to change what you do, but for the better.

I mean, did you really like spending such a gargantuan amount of time chasing non-supervisory employees to complete annual check-the-box training?

Or a managing a byzantine conflicts of interest disclosure system so you can spend all your time dealing with minor conflicts held by people who have no authority to make decisions anyway?

Or answering the same question about gifts and entertainment for the 10,000th time when you know the real answer is probably "UGH it doesn't really matter"?

No.

No one likes that, and if you say otherwise then you are made of lies and I WILL FIGHT YOU.

All of that is just paper-pushing. No one gets excited about it, no one gets inspired, and no one wants to have a job where you spend all your time apologizing for existing.

So instead of spending your time repeatedly chasing down that last person for annual training completion—a person who probably has zero authority to do anything bad in the first place—what this guidance says is that you should spend your time helping your most powerful (and therefore risky) folks figure out how to do their jobs the right way.

That is, instead of drudgery, you do design.

Which is good, too, because that's the first thing the DOJ says it asks under this new guidance: "Is the corporation’s compliance program well designed?"

And answering that question is fun.

Want to get started? We’re a compliance design company who transforms compliance training from “courses you take” to “tools you use to do your job.” Try it for free!