How *not* to write a compliance policy: tips from the DOJ's new antitrust guidance.

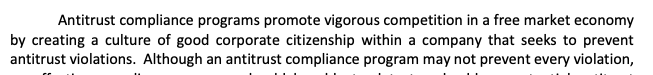

Writing a clear, easy-to-understand compliance policy is hard—so hard that the Department of Justice struggles with it, too.

For example: in case you missed it, the DOJ's Antitrust Division released its own version of the Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs last week; you can get that here. And since my job is compliance design, I read it Saturday morning on my couch while angrily muttering "what" and "no" over and over again.

Why? Because while this document's substantive rules are fine, it is also a nice exemplar of some of the worst choices we make in writing compliance policies—that is, it's a government guidance document that showcases where a lot of in-house policies go wrong.

So, while you're going to get bombarded with law firm updates that go into the substance of this new antitrust guidance (spoiler: meh), let's do something different.

Let's go over three things in this new DOJ guidance that undercut the effectiveness of the document—so you can avoid making the same mistakes when you draft your compliance policies.

Cool? Then here we go: three tips on what not to do.

#1: Don't lead with corporate cringe.

The new antitrust guidance leads off with this:

Woof. It goes on like that for an entire page.

Be honest: did you even make it through the entire sentence, or did you start skimming halfway through because you were like "ugh I know"?

If you skimmed it, consider this: you are already learning that it's OK to ignore some of the document on the first sentence. That is...bad.

And this is not a DOJ quirk.

The in-house equivalent is starting a policy with an "introduction" or "purpose" section laden with corporate boilerplate mad libs like "As a company committed to [NOUN], we have a strong commitment to [VERB]." I don't know how that trend happened, but no one sincerely committed to something starts a sentence that way; that's how PR people tell you to structure sorry-not-sorry apologies.

I think these cringe intros happen because everyone assumes that's how policies should start and so they kind of phone in some aspirational nonsense at the end of the project. And the correct response to that is NO and STOP IT.

Why?

Because you are signaling to your reader at the very beginning of the document that there is unnecessary stuff they can skip. And that's the best outcome: at worst, these intros come across as disingenuous lip service that make the whole thing seem like a farce.

So, cut it out. Get straight to the meat. If you feel you need to do this because the policy has a lot of technical requirements and you need a "why"—and that's fair— weave your explanations into the substantive requirements instead of as an awkward bolt-on up front.

#2: Don't use a "just kidding" qualifier.

The new antitrust guidance has this footnote on the first page:

This is a "just kidding" qualifier.

As in "oh, did you read this because you wanted to know how to do the right thing? JUST KIDDING, this means nothing because we reserve the right to do whatever the E.L. Fudge we want."

When you read something like that, you think "whatever, all of this stuff is politically enforced." And that's exactly what your employees think when these things appear in your policies, too.

Of course, it'll look a little different—the in-house version of this is putting catch-all and "we can't cover everything" clauses in policies to preserve your flexibility. And I know, it's super tempting to put stuff like this in your corporate compliance policies, because you can't anticipate every situation and blah blah blah.

But realistically, you have two options:

1. Suck it up, accept some risk and give people concrete guidance to promote some sense of fairness and transparency in how you enforce the rules.

2. Continue to make sure you have maximum flexibility and continue to be befuddled as to why everyone thinks of compliance as the company's secret police force.

Want a culture of compliance? Have fair, transparent rules and enforce them consistently. If you feel like you can't do this because you have too many unknowns, narrow the scope of your policy to things that you do know and revisit it later.

#3: Don't release it without double-checking that the organization makes sense.

Finally, the big one: I've litigated antitrust cases and I run a corporate compliance company and on my first read of this guidance I was like "wut" and "huh" because I kept getting tripped up on the organization.

This is because of the awkward way the "three fundamental questions" from the original Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs have been shoe-horned in. They appear here:

That probably makes you assume that these "fundamental" questions are going to be a pretty big part of the document.

And that's a fair assumption: in the speech announcing this thing the guy in charge of the Antitrust Division said that this section of the guidance was "framed" around those fundamental questions:

Aaaaaand it's not.

Those questions are never mentioned again.

Instead, that section is actually framed around three totally different "preliminary questions" and then nine elements of a compliance program. So, twelve different things.

Now, if you just ignore the "three fundamental questions" stuff, no problem—the document is pretty easy to follow. If, like me, you keep trying to figure out how all of these things fit into the three fundamental questions, because they made such a weird big deal about them early on, it is massively confusing.

My guess is this happened one of two ways:

Way #1. The Antitrust Division wrote the entire thing and then the Criminal Division was like "you guys have to reference these three questions because we're trying to make them a thing" and the Antitrust Division just responded with this:

But then the Criminal Division was like "no seriously" and then the Antitrust Division was like "ok fine but we're not rewriting the whole thing" and then the Criminal Division was like "ok fair."

...I have a rich interior life.

Way #2. It was organized around the three fundamental questions at one point, but far too many people worked on this through far too many revisions and no one with fresh eyes actually mapped out the organization before going live to see if it still made sense.

The second one is super common. We see this all the time, especially with policies that require a bunch of approvals or procedural steps.

Basically, everyone who works on the policy is so close to the document that they become blind to how it's actually structured. They know what they think it says, but that's not what it actually says, especially as it's grown and morphed and Frankensteined over multiple revisions.

To avoid this, there are basically two things you need to do: (1) have someone—a person, not a committee—be accountable for the policy and (2) have someone with fresh eyes map out the logic for you before you push it live.

Both those deserve unpacking, but that's a bit of a rabbit trail to the main point here—something to cover in another post!

Don't hide diamonds in horse poop.

Again, the substance of the new DOJ guidance is fine—except for that "just kidding" qualifier that makes the entire thing kind of meaningless. (But seriously, apart from that, it's fine.)

Similarly, the substantive rules in your company's compliance policies are probably fine, too. But that doesn't matter if no one reads them.

This is not about making your policies "pretty;" that's something lazy people say to justify why their stuff is unreadable. And as long as you think about things like readability and design as "making it pretty," you will end up with good-looking garbage like this.

Instead, this is about making the valuable parts easy to find.

Here's an analogy: imagine that your friend Gary tells you he has recently inherited a bunch of diamonds and you can have some for free. Because you are a good friend, you ask no further questions about the premise of this story and just go over to his house.

When you arrive, Gary greets you at the door and tells you that the diamonds are in the guest bedroom. You follow him there, but when he opens the door you take one look and freeze.

"Gary," you say, "this bedroom is filled with horse poop."

"Right," says Gary, "and...what's your point?"

"Well, where are the diamonds," you ask.

"In there," Gary says, motioning to the giant mound of poop.

You stare blankly at him.

"What did you expect," he continues, "that'd I'd have time to clean up before you came over? I'm already giving you diamonds; I don't have time to make the presentation pretty. You're smart, you find them."

That's what it's like when there are great substantive rules buried under corporate cringe, qualifiers that kill meaning, and confusing organization. Cutting that stuff out of your policies is not making your policies "pretty"—it's getting rid of all the crap that makes the good stuff hard to find.

And it's hard, but worth it: either you can get rid of all the crap, or you can make everyone else wade through it to try and find the diamonds—and most folks will just say "ew gross" and give up.

In fact, that is now one of the official Broadcat Principles of Compliance Design: "reduce the number of times employees say 'ew gross' and give up when interacting with compliance."

We've got tons of compliance communications, trainings, and other resources designed with just that principle in mind, and they're all in Compliance Design Club! You should check it out—you can even try it for free!