How to prove your compliance program works. [conference preview]

If you want to prove your compliance program works, you have to make a business case for it.

Because you work in corporate compliance, not Free Money Tree compliance.

And so it's not enough to say that your program reduces risk; it has to reduce risk in a way that saves more money than it costs. Otherwise your program doesn't work—it would be more efficient for the company to just do nothing.

This is not a new concept; it's basically how every corporate function justifies its existence.

But it's been muddied by the fact that there’s a glut of goofy advice on how to measure a compliance program.

You've probably been told to use a combination of benchmarking and employee surveys, for example, but these methods just measure what you do and how people feel about your program—not if anything you are doing actually works.

And if you don't even know if it works—let alone if it makes financial sense—you're in trouble.

Your budget will always be a mysterious thing handed down from Mount Olympus, and your headcount will be a nice-to-have.

And when the chips are down, your team and your projects will be on the chopping block, because you don't have a good way to defend them.

Don't let that happen to you—learn how to make a business case.

Business cases have numbers.

To be clear: when I say "business case," I mean that it has numbers, and those numbers are money, and they show that what you're trying to do will either save or generate more money than it costs to do it.

That is a business case.

By contrast, here are a bunch of things that are not business cases:

"This shows we're committed to compliance!"

"Blah blah blah values!"

"Companies with X outperform the market!"

"Our competitor has X!"

"It only costs $X!"

"Government fines are HUUUUGE!!!"

To get budget, you need to show why the specific things you want to do are financially worthwhile. None of those things do it.

A business case sounds like this:

“One of our risks was anti-corruption, and we realized that one of the practical things we do that touches on this risk is reviewing and approving invoices. Because if we’re flagging and rejecting the right type of invoice, we’ve massively cabined in our risk.

"We did some monitoring of our review process and found that we were approving around 100 invoices a quarter that had red flags in them. We figured out how many shouldn't have ever been approved, and how long it takes us to vet these after-the-fact through audits and investigations, and it was costing us $48,000 a quarter in loss and internal/external spend.

"We bought some new software that costs us $50,000 a year to license. That integrated into our finance system, and it reduced the number of bad invoices that were getting through by 90%.

"So before, we were losing around $192,000 a year. We now spend $70,000 a year—$50k for the software, and around $20,000 in remaining risk. Because even with the software reducing error by 90%, we still have some things getting through, and that costs us about $20k in loss and internal/exernal spend.

"And that means that our compliance initiative saves the company $122,000/year."

Note that this is specific in stating results, and then specific in turning those results into dollars. And note I am not using unpredictable, blockbuster fines or multi-year government investigations, just routine operational loss.

To turn this into a review of program-level effectiveness, you just roll up these initiative-by-initiative cases into a dashboard. That will give you a consolidated view of how your program reduces risk and saves the company money.

It's kind of like how your company's financial effectiveness is measured by rolling up all of the team results and division results and subsidiary balance sheets into a set of consolidated financials. It's not one big thing, but the sum of a bunch of little things.

In fact, the reason people probably like benchmarking and surveys is because it feels like it's just one big thing to do, and then you'll know if you're on point.

But it doesn't work like that; nothing in a complex organization works like that. You have to look at all the little things and add them up.

How to learn this.

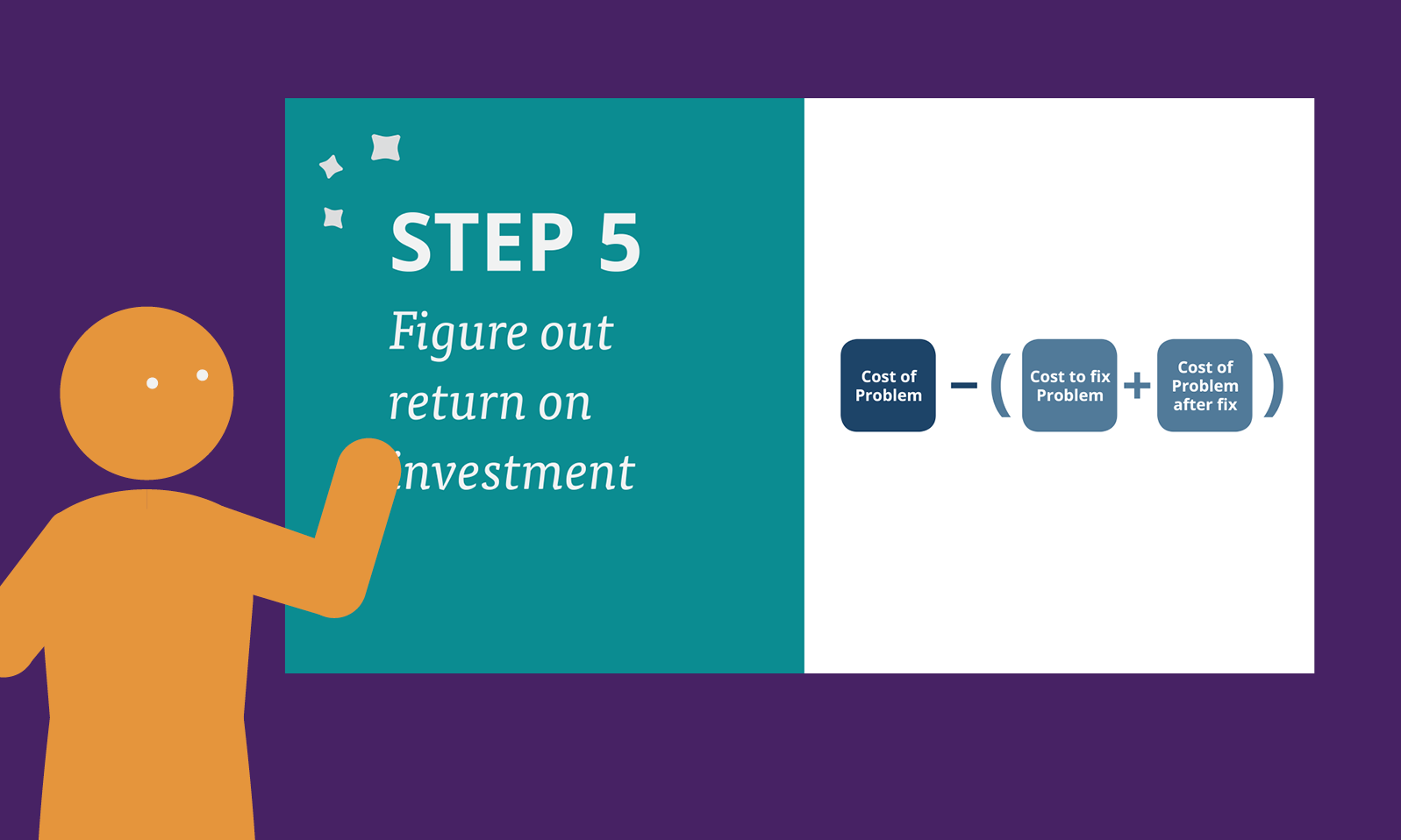

Now, the mechanics of how to build a business case—how to get all those measurements and turn them into dollars—aren't that complicated. There are just a bunch of steps involved.

And we’re going to go over exactly how to do that—how to make a business case—at the SCCE’s Compliance and Ethics Institute in October. We will walk through an example, and then we’re planning to pick someone from the audience and do another example live.

You should sign up to attend. Here’s the link.

So we’ll do that part live in October, and we’ve written a short book to walk you through it step-by-step, too.

Want a copy of the book? Drop us an email. We've made it easy for you, too—all you have to do is click this button and we'll send you an electronic copy.

Now, if you can’t make it to the conference and/or are too impatient to wait for our step-by-step guide, you can teach yourself on the internet.

This is not a secret, and it is not anything new. Creating a simple financial model is the first thing anyone starting a business has to learn, and there are a ton of resources out there. All we are doing is making it easy to learn it in the compliance context.

Do whatever works for you—but do it.

Because if you want a seat at the table, you have to be speaking the same language as the people who are already sitting down. And when you work in a business, that language is a business case.